The following is an account of life in Dryden during the Great Depression of the 1930s. Included are firsthand accounts of growing up during that era.

The names of the people who have shared their recollections are used and retained in the article in order to authenticate those stories. With any stories of hardships, there has been no attempt to link one's difficulty with one's socioeconomic status at the time.

During normal economic downturns in any free market economy, the lives of young people are not dramatically changed unless a parent or guardian has suffered a job loss. However The Great Depression had such a profound effect on the world economy that everyone, regardless of age or economic status, was affected by it in one way or another.

When asked to first describe the Depression, Mabel Franklin, Edna Wilson, Tom Leach, Trudy (Hutchison) Hotson, all stated that there was no money at the time. Edna and Mabel both emphatically stated that people of today cannot understand this because they have not lived through a similar period. The statement that there was no money can probably be interpreted as the collapse of the local economy.

Ken Collins book Oatmeal & Eatons catalogue sheds light on the early stages of The Depression and how the community of Dryden was affected. Within a few short weeks of the stock market crash of October 1929, many of the orders for paper products were cancelled. In order to deal with this excess inventory, Collins writes that every square foot of space at the Mill became storage areas filled with unsold paper products. This resulted in immediate layoffs at the mill which caused a further expeditious drop in economic activity in the Dryden region.

As important as the economic well-being of the Dryden Paper Company, was the financial health of the many sawmill operations in the region. According to a written account dictated by the late Bill Franklin, one such operation was the Indian Lake Lumber Co. at Osaquan. Osaquan was located five miles west of Ignace. At such a lumber camp, a working man could earn up to twenty-six dollars a month plus room and board. All the harvesting and cutting was done by hand and delivered to the various sawmills by teams of horses. As written by Franklin, sawmills such as the Indian Lake Lumber Co. employed up to 400 men. Feeding those men went a long way in supporting the local farmers.

According to Tom Leach (whose father was one of the Indian Lake Lumber Company's superintendents), the main destination for company's lumber was the Chicago area. Once the economic slowdown of 1929 took hold, shipments of lumber to the United States were severely constricted. By 1931, the main operations at Osaquan were shutdown, leaving those 400 employees out of work and with basically nothing. Only a handful of employees remained working at the planeing mill until 1936. At that time, all of the remaining operations of the company were permanently closed. According to Tom Leach, those who stayed in Osaquan after 1931, almost starved.

Therefore, it was the closure of many of the sawmills in the area and the limited operations at the Dryden Paper Company that contributed to the collapse of the local economy.

As the Depression progressed, orders at the mill decreased further. During the darkest period of the Depression (1931-1933), Ken Collins records that orders at the mill were almost non-existent and the mill was often closed for 3 weeks at a time. According to Collins (pg 146), the Dryden Paper Company, in consideration of its employees, paid the workers in advance for three days work. This advance was deducted from future earnings. In addition, the Company kept the basic rate of pay at forty-one cents per hour during the entire period of the Depression. Jock Ferguson's father worked at the Dryden Paper Company during The Depression and Jock remembers the advance pay his father received to help make ends meet during the most difficult times.

Charlie Rankin and Mabel Franklin have mentioned that one of the greatest influxes of people to the Dryden area were from the Western Provinces during the severe drought of the 1930s. According to Mabel, the prairies are not a natural environment for subsistence living. There are few lakes and trees and with the drought and insect infestations, it was impossible to grow anything and survive. As a result, many young families who migrated west during the 1920s found themselves settling in the Dryden area during the 1930s. An innumerable number of local people have mentioned that their families moved to Dryden during the late 1920s and the 1930s.

Dryden was much better off in comparison to other regions of the country. With the forest, fertile soil and the abundance of lakes, it was possible to survive by growing a garden, engaging in berry picking, and hunting and fishing. The large supply of wood was used for heating the homes and for cooking.

As a child Helen (Austin) Van Patter remembers the difficult times that people experienced in the Detroit-Windsor area. Helen said that "People were just scraping by trying to find food to eat. It was very bad in the cities". Her grandfather, who lived in Dryden, invited her family to come and live here because "one could hunt and fish and live off the land". As a result, her family relocated to Dryden in 1930.

Edna Wilson tells an interesting story of her family's relocation to Dryden in the 1920s. Edna, her mother and her sibling arrived in Dryden ahead of their father John Taylor. To make the trip from Saskatchewan, Edna's father rented a box car and made the thirty-six hour train ride in the box car along with all of his farm animals. He started off in Saskatchewan with 150 chickens, two horses, two cows and some younger calves. He was forced to sell fifty chickens in Winnipeg to pay for the trip to Dryden. He rode in the box car with the animals to ensure that they would be properly fed and watered.

In addition to those newly settled in Dryden, there were a large number of transients passing through the region. These drifters came from all walks of life. Milly (Findlay) Lappage, Charlie Rankin, Mabel Franklin, Trudy (Hutchison) Hotson, Irene Park and others have vivid memories of those dirty, tired hobos who rode the rails looking for work. It must be noted that no individual has recounted a story of thievery or of violence with respect to those hobos.

According to Trudy Hotson, the train travelers would leave markings at rail crossings where food, help and temporary work could be found. The Hutchison family fed many such individuals. If Trudy's father was home, the men washed outside and ate in the kitchen. If Trudy's father was working in the fields, the men would eat out on the veranda.

Milly Lappage remembers a man of African descent looking through her living room window. When the man was approached, it was discovered that he was just looking for something to eat. Mildred (Wright) Drew recounts a story, when at the age of eight, she accepted a man into her home and fed him. Later, her mother was livid with her!

Others have recounted stories of the work these transients did in exchange for food. They would spend long hours cleaning a barn, cutting wood and other heavy labour in exchange for something to eat. Sometimes that meal was just a stale loaf of bread.

Trudy Hotson remembers a popular hit song during that era:

May I sleep in your barn tonight, mister?

For its cold lying here on the ground and I have no tobacco or matches.

I am sure that I can do no harm.

If there was very little money to purchase necessary good and services, then bartering became the order of the day.

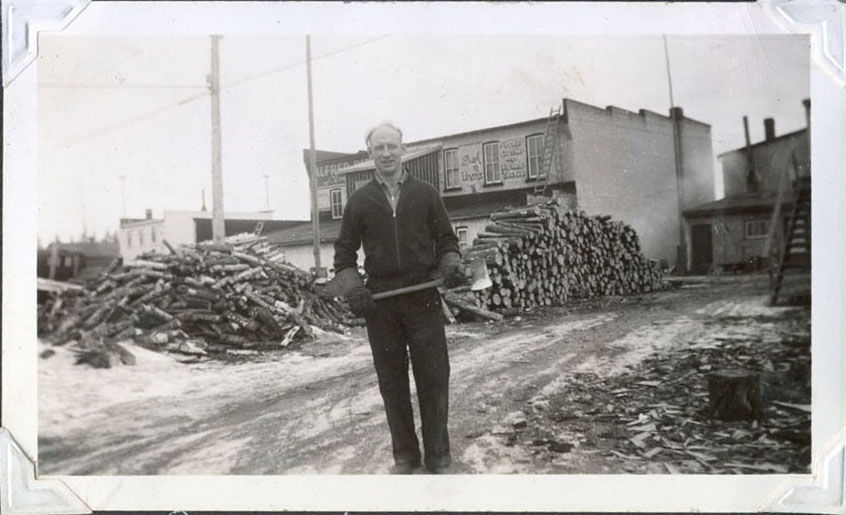

The following picture is of Claude Stansfield. The Stansfield family operated a bakery in Dryden during the 1930s and 1940s. Large piles of wood were commonly seen in Dryden during that era. The picture was provided by Milly (Findlay) Lappage

The abundance of wood in Northwestern Ontario led it to become a commodity for bartering. As mentioned, transients to the area would often chop wood for hours at a time in exchange for a meal.

Many local farmers had bartering arrangements with the town merchants. They would exchange beef, pork, veal, turkey, geese, eggs, honey milk and cream for basic staples such as sugar, coffee, flour, salt and canned goods. Sugar and flour were bought and exchanged in one hundred pound bags.

Trudy Hotson has recounted a few happy narratives of the bartering that took place during The Depression. Trudys mother received a cheque from Dr. Dingwall with a letter explaining that she had more than paid for the family medical expenses. Mr. Reid, the town barber also wrote a cheque to Trudy's father with the explanation that her father would not live long enough to have that many haircuts.

There were varying degrees of poverty experienced by young people. Children whose fathers worked at the mill needed to find other means of supplementing their salary in order to provide the basic necessities to their family. Those whose fathers worked as superintendents or foremen at the Dryden Paper Company or at one of the logging camps lived more comfortable lives. Those children whose parents did not have employment or who did not have both parents at home suffered from hunger and from the cold.

The following picture was taken in 1932 (the height of the Great Depression). The children attended Rice Lake School. Pictures of Rice Lake school were provided by Charlie Rankin.

Trudy Hotson recalls students eating plain ketchup or pickle sandwiches for lunch. Harry Dezoba remembers one family making onion sandwiches for lunch at school. Children whose fathers worked as a foreman were known to have a ham sandwich, a banana and sandwich cookies for lunch.

Mabel Franklin remembers children rarely receiving gifts on their birthdays or at Christmas time.

Jock Ferguson remembers the rubber boots that he wore during the winter and how cold his feet were. Though he does not have memories of going hungry, Jock does remember eating oatmeal two or three times a day.

Tom Leach has mentioned that in the summer of 1936, his softball team was invited to Wabigoon to play the local team there. Only three of the fathers had cars to drive their sons to the tournament.

Trudy Hotson remembers the many hand-me-down clothing items that she wore until she finished school. But the greatest problem for her was footwear. The local shoe store did not participate in the barter system, and she was forced to wear a pair of crummy runners. Trudy was able to tailor the hand-me-down clothes to her taste, but the footwear was impossible.

Victor Smith and Maudie (Smith) Lundmark have very vivid memories of the poverty that they lived through during The Depression. Cold and hunger were more often the norm than the exception. In 1929, Victor's father found employment as a bricklayer at a paper mill in Pinefield, Manitoba. Early in 1930 the family of eight children moved to Winnipeg to be closer to their father. Unfortunately, their father's pay was not enough to meet the family's basic needs. To make matters worse, the family had not lived long enough in Manitoba to qualify for provincial relief. Within a short period of time, the Manitoba relief agency purchased one way tickets for Victor, his mother Emma Smith and his seven siblings to return back to Wabigoon. As the train was leaving the Winnipeg station, Victor's father was standing on the platform waving goodbye to his family. That was the last time that Victor saw his father.

Pictured here is Mrs. Emma Smith after blueberry picking. Berries were an essential for survival in Northwestern Ontario during The Depression

One must only commend Emma Smith for her struggle to raise and feed her eight children. Gardening was difficult as the clay soil in the Wabigoon area hardened with rain. To help feed his family, Victor was deer hunting at the age of twelve. He snared a variety of small game. According to Maudie, all types of fish including suckers and jackfish supplemented their meals. To raise money Victor sold squirrel hides for ten cents each. In winter, Maudie remembers wearing hard rubber boots that offered little protection from the cold. In order to receive their relief payments, it was mandatory that the children attend school. The two and half mile walk to school in the dead of winter wearing rubber boots with no lining made the walk all the more difficult. After every walk, the hard rubber boots left painful red rings around the childrens' ankles. Often, the children arrived to school and the custodian had not started the wood fire to heat the school. The single room school was so cold that the fifty students were forced to wear all of their outdoor clothing in the classroom. The cold in the classroom made it difficult to hold a pencil and write anything down on paper.

To this day, and to the amusement of her children and grandchildren, Maudie keeps a well stocked freezer, with a promise to never go hungry again.

It is very interesting to note the wages that were earned and the prices that were paid to purchase and sell various goods and services before, during, and after The Depression.

According to the late Bill Franklin, a man working at a logging bush camp during the 1920s was paid twenty-six dollars a month plus room and board.

Before The Depression, the Dryden Paper Co. bought wood from the settlers and paid them seven dollars and fifty cents per cord, which included delivery to the mill. The cutters were paid two dollars per cord. That left Bill Franklin and his brother five dollars and fifty cents per cord. With a good team of horses, they could haul one and half cords per trip and they made about five trips a week. At the time, they could live quite well with that.

Starting in 1926 and continuing through The Depression, Mr. Wilson, then manager of the Dryden Paper Co., offered a prize of twenty five dollars to the student with the highest standing in the high school matriculation exams.

Howard Wilson has recorded that after 1933, the Dryden Paper Co. started to buy wood again from settlers. According to Wilson, they were only paying three dollars and fifty cents per cord, which was cut and delivered to the mill.

Victor Smith also remembers selling and delivering cut lumber to the mill. He was paid four dollars and fifty cents per cord. This occurred during the mid 1930s.

Howard Wilson has also stated that when the work camps opened in the mid 1930s, they paid ten cents per railway tie. The cutter was required to hew the tie, clear the road and put the tie at the roadside. Depending on the conditions, a man could do as little as two ties or as many as twenty railroad ties in one day.

Bill Franklin noted that during the dust bowl of the 1930s, settlers to Northwestern Ontario could file for a homestead paying two dollars for 160 acres.

A neighbour of Mabel Franklin, his wife and two daughters were able to live on thirty-five dollars a year. They sold and bartered farm goods for grocery staples.

A 100 lb bag of flour cost one dollar ninety-five cents. A 100 lb bag of sugar sold for five dollars and fifty cents. A ten pound box of macaroni cost thirty-five cents. A ten pound pail of syrup was seventy-five cents and thirty pounds of beans cost fifty cents. (Franklin)

Edna Wilson has told the story of how her father had butter to sell, but was only offered ten cents a pound. At the same time, he needed axel grease, but the asking price was ninety cents per pound. So, he improvised and used his own butter as axel grease.

From the start of The Depression, and throughout the 1930s, The Dryden Paper Co. kept the basic wage at forty-one cents an hour. (Ken Collins).

In 1930, Frank Wiilard and Sybil (Thorp) Willard purchased a house in Dryden and the mortgage was forty dollars a month. (There was no running water until 1937). As The Depression deepened, making the monthly payments became very difficult for many homeowners. The government passed a law that stated that as long as one was paying the interest on the debt on one's house, the house could not be taken away. This reduced Frank and Sybil's monthly payments to just ten dollars a month. (Willard)

The Rutter's restaurant in Dryden sold homemade pie for ten cents a wedge, and coffee was five cents a cup. Twenty-five cents, an amount that was hard to come by, bought one a whole pie. Mrs. Rutter often paid workers one dollar to cut a cord of wood for the restaurant. (Franklin)

In 1930 Sybil Willard was paid $100 per month as a teacher at Albert Street School. (Willard) In 1941, the starting salary for an elementary school teacher was $900 per year. (Betty Hawke).

Stansfield's Bakery sold an ice cream cone for five cents, a soda for ten to fifteen cents and a banana split for twenty-five cents. (Tom Leach)

Mabel Franklin sold fresh blueberries for four cents a pound. In 1937 she sold butter for thirty-seven cents a pound, and eggs for between twenty-five cents and thirty-five cents a dozen.

During the 1930s, Sybil Willard purchased eggs from the Norgate farm for twenty-five cents a dozen. Milk was ten cents a quart.

Victor Smith sold squirrel hides for ten cents each during the 1930s.

In 1937 Harry Dzeboa paid ten cents to watch a Saturday matinee at the local Strand theatre.By 1947 Alice (Cook) Bloomfield was paying twenty-five cents to watch a movie at the Strand theatre

By the mid to late 1930s a farm hand working at one of the many Oxdrift farms earned five to ten dollars a month. (Gilbert Coutts)

By the start of the war, Maudie (Smith) Lundmark earned five to ten dollars a month while employed as a waitress.

In 1922, after completing Grade 8 studies, Frank Willard entered the services of the Royal Bank as a junior clerk. He was paid forty dollars a month with forty dollars deducted per year for the bank pension fund. (Willard). In 1938, as a high school graduate, Leonard Leach earned twenty-eight dollars a month working at the Royal Bank in Dryden. His salary was raised to $30 a month in 1939.(Tom Leach)

A new Ford V-8 sedan cost about five hundred dollars in 1935. (Tom Leach).

A new deluxe Chevrolet cost just under $1,100 in 1940. (Harry Dzeboa)

The above stories are just a fraction of the stories told by the many seniors who grew up and lived during the difficult economic times of the 1930s. Knowing and understanding their stories, is our hope of not having to relive those events.