Gordon was hired on August 1, 1957 as a clerk-scaler at camp #1 North Division which was located 40 miles north of the present location of the Dryden ski club.

Norman MacMillan was still Woods Manager in the late 1950s. Fred Morton was Divisional Superintendent and Bill Beatty was assistant Divisional Superintendent for the North Division.

When Gordon was hired there were approximately forty wood cutters at camp #1. The camp foreman was Alex Kozowy and Jim Cox was the strip boss (assistant foreman).

The camp foreman was responsible for all global operations at the camp. He used his experience to determine the best layout for the logging operations that were to occur. For instance he would specify where the roads into the forest would be built so that the harvested wood could be transported to the mill. Additionally, he stipulated the location where the wood would be bucked (cut to length) and piled. These sites were called landings or skidways.

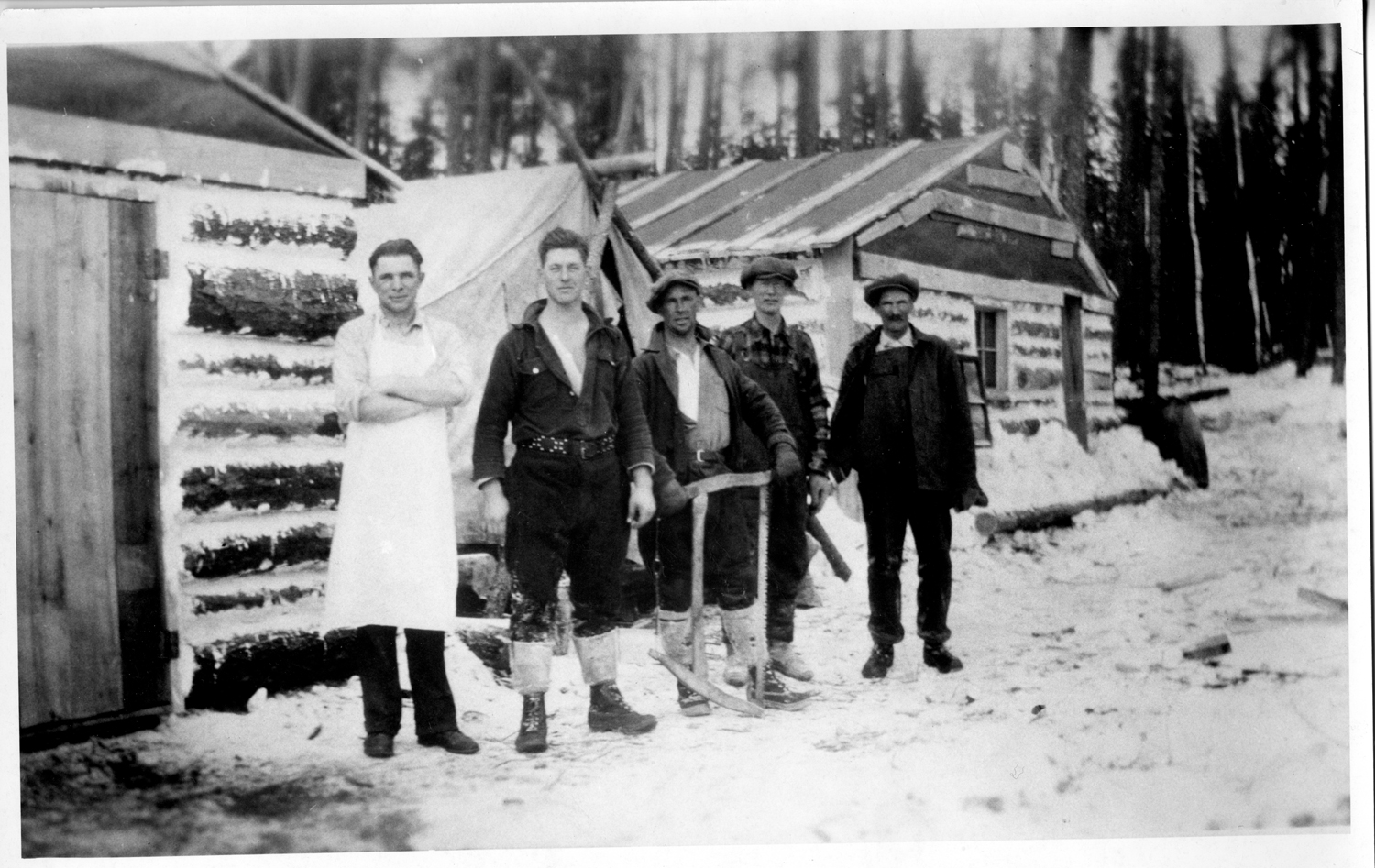

This picture dates to 1932. The names left to right are: Mike Delani, Bill Franklin (Gordon's father), Lorny Weaver, Bob Coates, Charlie Morton

The strip-boss (assistant foreman) got his name from the task of laying-out the boundaries of the cut-blocks or strips assigned to the cutters.

As a scaler, Gordon had to measure the amount of wood cut and piled by the wood cutters. Payment was made by piece-work in those days. One was paid for how much was produced, not by the number of hours worked. Gordons clerical duties included running the Van. The Van was the little store in the camp that would sell socks, swede saw blades, tobacco and other necessary goods to the bush workers. It is of interest to note that at that time, tailor made cigarettes were prohibited at the camp. Cigarettes hand-rolled from thin rice paper would go out as soon as you set them down, whereas factory or tailor-made cigarettes would continue to burn and could start a forest fire.

To measure and record the amount of wood cut by the cutters, the clerk-scaler used a measuring stick that was divided into feet and units of 1/10 of a foot. A cut cord is a pile of wood four feet in width, four feet high and eight feet in length. Actually, a nominal 8 foot stick had to be cut 100 inches long. The extra four inches was called broomage, and it dates back to the river drives where the logs bumped against each other, spoiling the ends. Though logs were towed across the Wabigoon and Dinorwic lakes and this was much gentler on the wood, the tradition still held for many cutters to add an extra four inches to the length of the logs. The Provincial government scalers accepted 100 inch logs as eight foot logs.

Approximately one-half of the wood harvested at camp #1 was produced by the strip-cut method. Strip cutting was a one-man operation whereby the workman would cut and pile by hand, rows of one-cord piles, usually in parallel strips 66 feet wide. The strip-boss layed out the boundaries of these strips, generally located in flat black spruce swamps, although in some cases, jackpine on sandy terrain was harvested by the strip-cut method for hauling during the summer season.

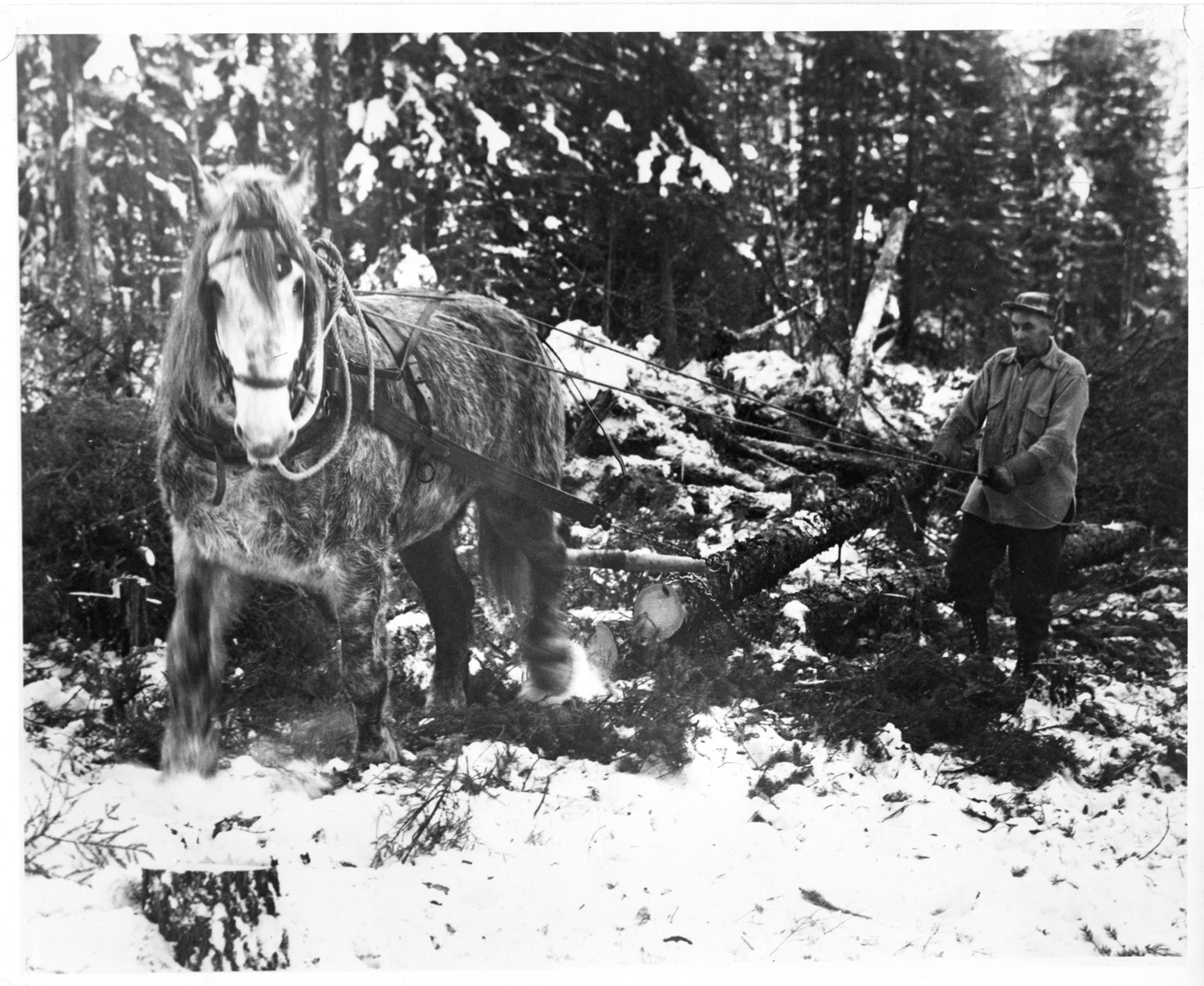

The other one-half of the annual volume was cut and piled into ten-cord (or larger) piles. This operation was done by a crew of two men and a horse. (In bush lingo, the cut, skid and pile method was called gyppo. One man would fell (cut down), de-limb the tree and remove the un-merchantable (smaller than three and one half inch diameter) top. Using the horse, the second man would skid the tree to the processing area called the landing or skidway. Here he measured and cut the tree into the required 8-foot lengths and piled them by hand. Some legendary crews had their horse so well trained that, after the workman had hooked the skidding chain to the felled tree, the horse would walk along the skid trail alone, to the landing. There the other workman would un-hook the tree, turn the horse around and send him back (all alone) for another tree.

The worker here is using a horse to skid the felled tree to the landing. Horses worked hard during the time period but were well taken care of. At a logging camp, the horses were taken care by the "barn boss". Use the scroll bar to see the entire image

According to Gordon, there were only three swede-saw cutters at camp #1 in 1957. The rest of the cutters were using gasoline-powered chain saws.

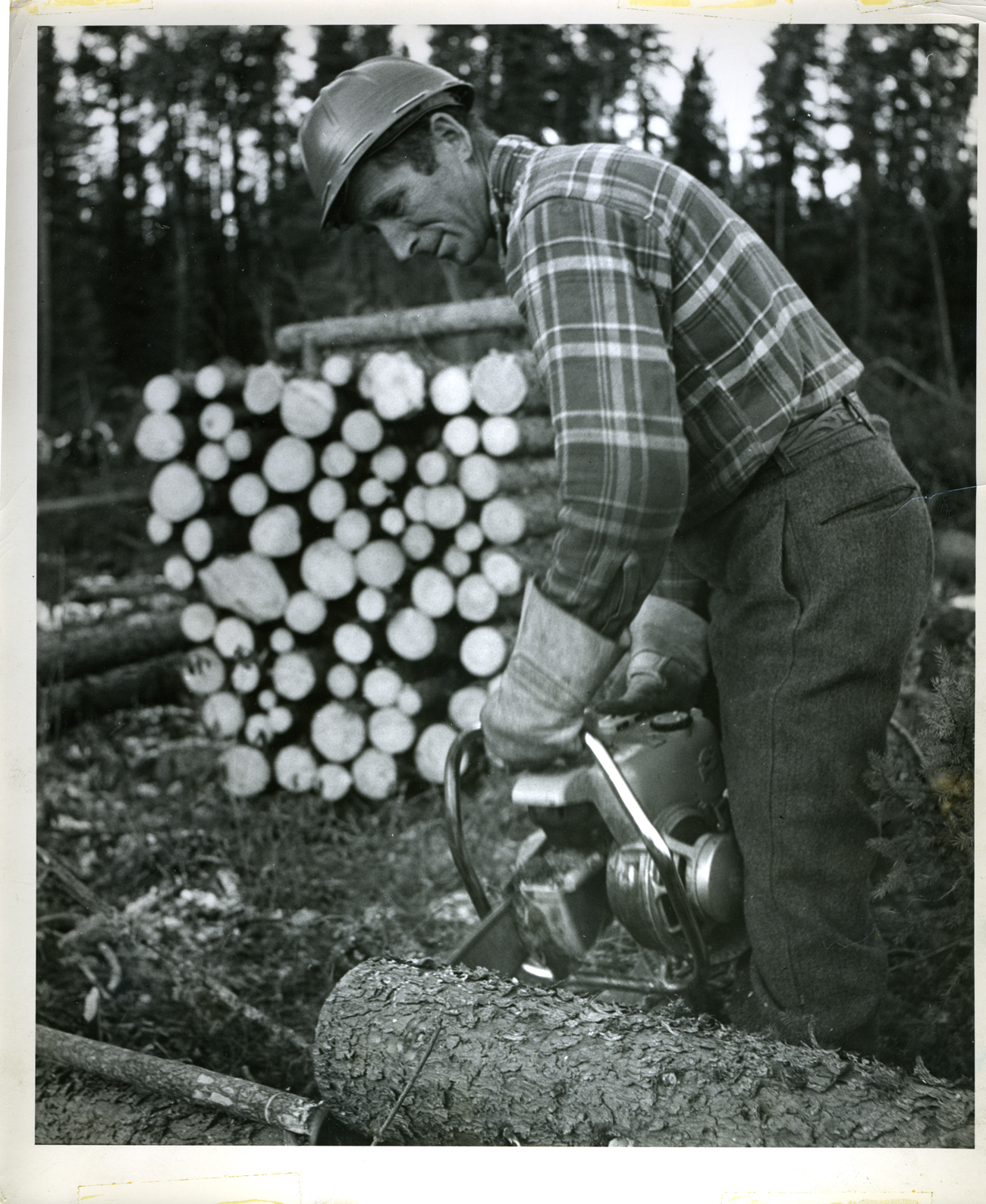

The chainsaw used here is a 1955 IEL Pioneer, manufactured and sold only during 1955, but it was a good performer and was popular for several years. This model differed from the 1954 model in that the "airplane carburetor" was introduced for the first time. The housing for the motor is one solid piece from the muffler at the front and including the filler cap for the gas near his right thumb. The "swivel" has disappeared. Power saws did not have automatic oilers to lubricate the metal against metal cutter chain where it ran in a grove on the cutting bar. The operator had to pump a manual oiler lever located just under his left thumb. In this picture the operator has just completed his cut and the eight foot piece to the left has dropped down. You can see his measuring stick resting on the piece he just cut off. What is interesting was that the measurement of a cord of wood changed when Canada went metric during the mid 1970s. A cord of wood was 4 feet by 4 feet and 8 feet long, which measured to 2.41 cubic meters. After the adoption of the metric system, the company decreed that a cord of wood was 2.5 cubic metres meaning that the logger had to deliver 3.7% more wood for the same price. During the late 1950s, the lumberjack was paid on a piecework rate, about seven dollars a cord. Many legends have been told of men cutting and piling five or six cords of wood, but most men were only able to harvest three cords of wood per day.

The introduction of the one-man-operated, gasoline powered chainsaw into the Boreal Forest has had such a significant impact upon man-day productivity and on log harvesting methods and systems that it deserves its own section in this story.

Though most of the evolution took place in the decade of the 1950s , the legend goes that in 1937, Andreas Stihl who was German, introduced his chainsaw to Canada. He had to drive completely across the country before he sold fifty saws, all in British Columbia. It revolutionized man-day productivity for the fallers and buckers on the West Coast. Then the War started and it became unfashionable to buy manufactured products from the Germans. Scores of small manufacturing companies sprang up on the west coast of Canada and the U.S that imitated the chainsaw designed by Stihl. IEL (Industrial Engineering Limited) built an almost exact copy of the Hitler Saw. Necessity being the mother of invention, more power and less weight was required. Innovative, giant strides were made in a very short period of time that increased power and decreased weight. Motorcycle and outboard motor manufacturers recognized these developments and bought up many of the new chainsaw manufacturing firms to get their technology. Only a dozen or so of these companies persisted (trade names that we still recognize). Eventually, sometime in the late forties the one-man saw started to make noises in the Boreal Forest in central and eastern Canada. A generation of young men (mostly returning Veterans) appeared who would rather operate a machine than swing an axe or pull on a cross-cut saw.

There were three parallel improvements in the technology that operated chain saws. With first generation chain saws, the gas was gravity fed into the carburetor, meaning that one could not turn the chain saw on its side to fell a tree. Early solutions to this problem were to have a swivel point between the chain saw and the motor. The operator would turn the chain 90 degrees allowing him to fell a tree while keeping the gas tank and carburetor in an upright position.Eventually, in 1955 the airplane carburetor appeared which allowed the motor to continue operating in any position. A second problem with early generation chain saws was that they were "gear driven" and utilized a manual clutch. The gear reduction meant that the chain moved too slowly to effectively de-limb a tree and the manual clutch caused the chain saw to stall quite frequently. The second generation of gas powered chainsaws were "direct drive". These models used a centrifugal clutch that was similar to an automatic transmission in a car. Therefore, the fast moving chain could successfully de-limb a tree. A third improvement to gas powered chain saws was the mechanism used to start the machine. To start the older generation of chain saws (late 1940s), one wrapped a rope around the sprocket and pulled hard to start the motor. These older chain saws were replaced by chain saws that had a rewind starter. With these models the rope that started the motor was pulled automatically into place by a spring.

After the late 1950s,improvements to chainsaws continued but not as quick as earlier years. The overall weight of the machines decreased, power was increased, and noise and vibration decreased. The ??chain-brake?? greatly decreased the incidence of horrible saw-cut accidents.

The late 1950s and early 1960s brought about innovative changes to the technology of harvesting trees. Along with mechanized methods of cutting trees, the Dryden Woodlands Operation was well ahead of other Woodlands operations in the introduction of mechanized skidders. Two mechanical skidders that were introduced in the 1950s were the Anderson Woodhawk and the Johnson skidder. The Johnson skidder was developed by local resident Henry Johnson. In its most basic form, the Johnson skidder was a clam (used for grabbing pulp wood) mounted on the back of the frame of a bulldozer. The Johnson skidder was used to haul pulp wood that was cut and arranged in one cord piles out to a haul road where it would be loaded onto trucks and hauled to the mill. The Wood Hawk did the same job, except that it was towed behind a crawler tractor.

Other machines introduced during that time period were the Drott loader, which was an attachment mounted on the front of a good sized tractor that would go into the bush during any season and grab a cord of wood (either from strip-cut piles or from the larger gyppo piles) and bring it out to the trucks waiting on the company built roads. Drag lines saw a lot of use in Dryden. A drag line was a crane with a long boom that had a cable and clam and was able to pile wood onto the top of a pulp truck. In the Dryden operation, draglines were used for loading gyppo piles, but they were also used for loading strip cut piles. On good ground, a truck road was built between every two strips so the dragline was taken very close to the stump in the bulldozed strip system.

J.K. Robinson, (Mechanical Superintendent of Woodlands and later General Manager of Dryden Paper Company) played a very pro-active role in the introduction of mechanization to the cutting and harvesting operations here. He was fully supported by Ken Nielson, the Woodlands Manager at the time. These two individuals oversaw the establishment of many mechanized skidders and loaders, making the Woodlands operation of the Dryden Paper Company one of the foremost leaders in terms of mechanization.

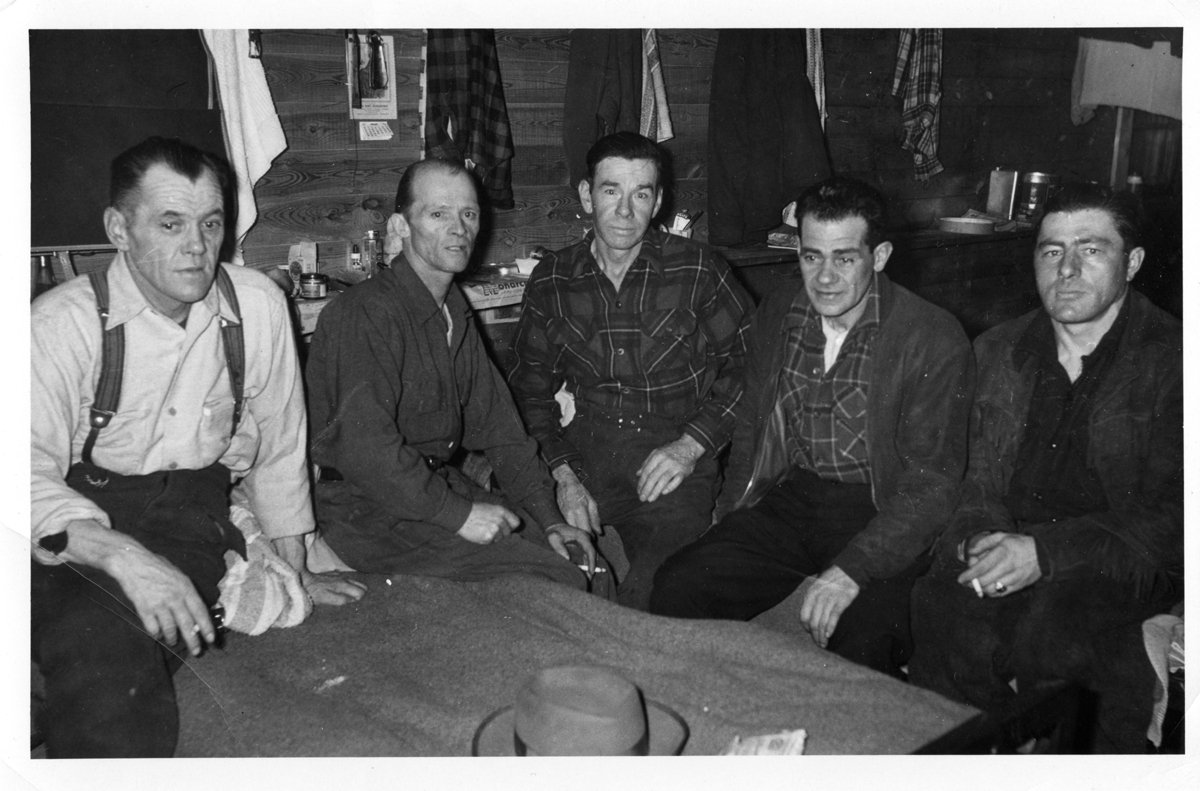

Gordon Franklin has also shed light on the life for the average worker in the logging camps during the 1950s up to the 1970s. For a camp with forty bush workers, there was a cook and two cookees, or cooks helpers. Larger camps had a second cook and even a baker. When Gordon first started working in 1957, there was a waiter (Cookee) who served the men their meals. As time progressed, the waiter was eliminated and the workers served themselves, very similar to the cafeteria style restaurants of today. Prior to the mid-fifties, in the bunkhouses there were double bunks, one man slept above and one man below. These double bunks, along with the wood stove heaters, made for an uncomfortable sleep for both bunkers. The persons in the top bunk were usually too hot, and the persons in the lower bunk were too cold during the night. By the mid 1950s, the double bunks had disappeared, which made for a less crowded bunk house.

These bush workers worked extremly hard in difficult weather conditions. Their faces tell the story of hard work. For many people in the Dryden region, lumber camps and mining camps were the only jobs available to them

Along with the bunk houses, the cookery, and office was a barn with ten to twelve horses, along with an employee, called a barn boss who cared for the horses. To maintain camp cleanliness was an individual named a bull cook.

The following are pictures of a Drott Loader. The Drott loader was a conventional crawler tractor that was manufactured by International or Caterpillar. The tractor was the same as tractors used on highway construction, except it was equipped with a lot of bush guarding and a safety canopy over the operator's head. The clam for lifting wood was built by Drott Manufacturing in Wisconsin.

The worker has a pickaroon in his hand for straightening the logs on the load. The birch picket, or rear stake, was normal at the time, although it looks primitive today.

Three more photographs illustrating how pulp wood was loaded onto the trucks for shipment to the Pulp and Paper Company